Cranial Cruciate Ligament Tears in Dogs

Helping your dog get back to a happy, pain-free life.

Cranial cruciate ligament (CrCL) tears are one of the most common causes of back-leg lameness in dogs. If your dog is limping, reluctant to jump, or suddenly won’t use one of their back legs, a CrCL injury may be the reason. This page explains what a CrCL tear is, how we diagnose it, and the treatment options available, so you know what to expect and how we can help.

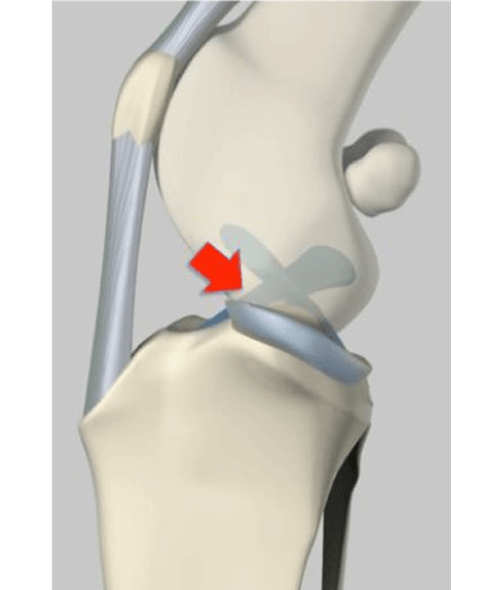

What Is the Cranial Cruciate Ligament?

The cranial cruciate ligament is a strong band of tissue inside the knee (stifle) joint.

Its main jobs are to:

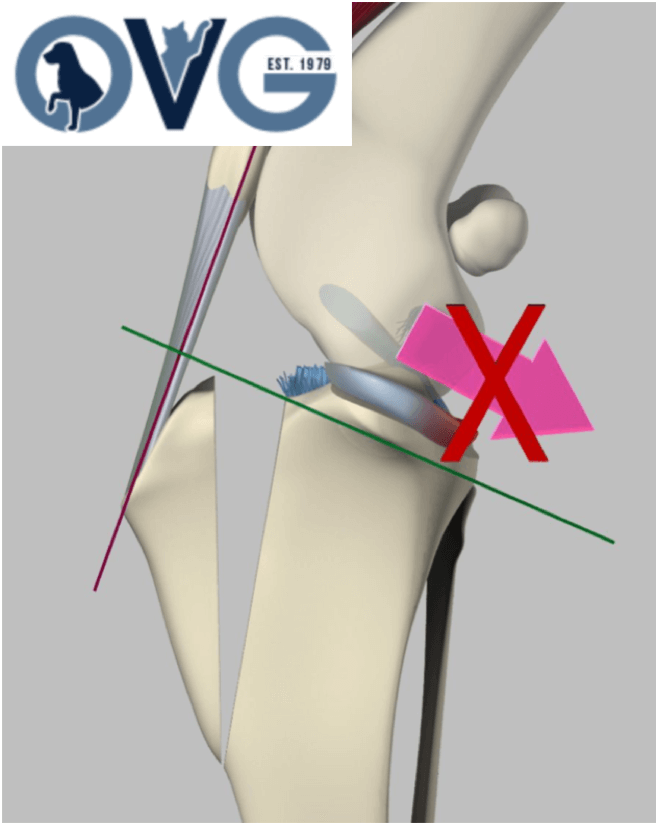

- Prevent the shin bone (tibia) from sliding forward under the thigh bone (femur)

- Help stabilise the knee during walking, running, and turning

- Protect other structures in the joint, including the meniscus (the “shock absorber” cartilage)

In humans, a similar ligament is called the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), which is why you may sometimes hear people call this an “ACL tear” in dogs.

Why Do Dogs Tear Their CrCL?

In many dogs, the ligament doesn’t suddenly snap during a single accident. Instead, it weakens gradually over time due to a combination of:

- Breed and genetics (some breeds are more prone – e.g., Labradors, Rottweilers, Boxers, spaniels)

- Body weight (overweight dogs put more strain on their joints)

- Conformation and tibial plateau angle (the shape and angle of the bones in the knee)

- Age-related changes in the ligament itself

Because the ligament is slowly degenerating, it can then tear partially or completely during normal activities – such as running in the garden, jumping out of the car, or even just slipping on the floor.

Important point for owners:

It’s usually not your fault and not simply due to one wrong move. It’s more like a rope that frays over time and eventually breaks.

Common Signs of a CrCL Tear

Dogs with a cranial cruciate ligament tear may show:

- Sudden lameness in one back leg

- Toe-touching or non-weight-bearing on the affected leg

- Difficulty rising, jumping into the car, or climbing stairs

- Stiffness, especially after rest

- Sitting with the leg held out to the side

- Muscle loss on the affected thigh if the problem has been present for a while

- Swelling around the knee joint

Sometimes the lameness improves with rest and pain relief, only to return. This is typical of partial tears that worsen over time.

If both knees are affected (which can happen), your dog may appear generally weak in the hind end rather than obviously lame on just one side.

How We Diagnose CrCL Tears

At your dog’s appointment, we will:

- Take a detailed history

- When did the lameness start?

- Was there a specific incident, or did it come on gradually?

- Does it worsen after exercise or rest?

- Perform a full orthopedic exam

- Use imaging where needed

- X-rays (radiographs) can’t show the ligament itself, but they do show bone alignment, joint swelling, and arthritic changes.

- In some complex cases, further imaging (such as ultrasound, CT, or MRI, or arthroscopy) may be recommended.

In many dogs, a CrCL tear can be strongly suspected from history + physical exam, then confirmed with X-rays and, in some cases, during surgery.

Why Treatment Matters

A torn cranial cruciate ligament causes:

- Pain and lameness

- Instability in the knee, allowing the tibia to slide forward

- Damage to the meniscus, the shock-absorber cartilage inside the joint

- Osteoarthritis (arthritis) that worsens over time

Without appropriate treatment, most dogs will:

- Continue to limp or be intermittently lame

- Develop progressive arthritis, leading to more pain and stiffness

- Have a reduced quality of life and may struggle with normal activities they enjoy

Early and appropriate treatment helps:

- Reduce pain

- Stabilise the joint

- Protect the meniscus

- Slow down arthritis development

- Restore as much normal function as possible

Treatment Options

We tailor treatment to each dog, considering size, age, activity level, other health issues, and budget.

- Surgical Treatment

For most medium and large dogs, surgery is recommended because it provides the best chance of long-term comfort and function.

Common surgical options include:

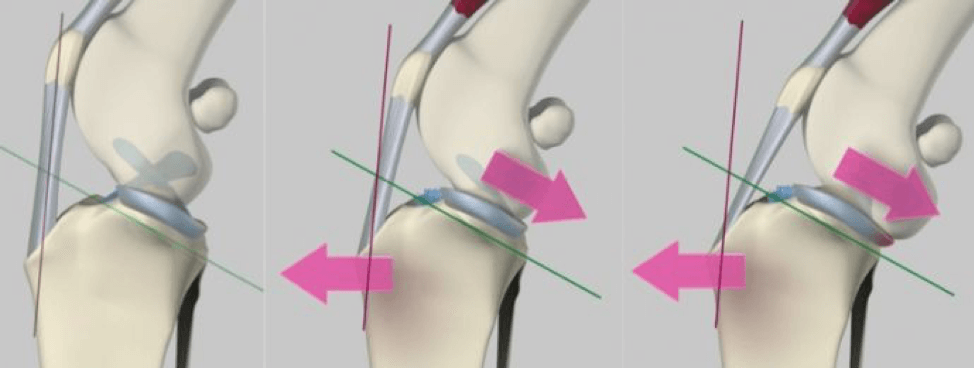

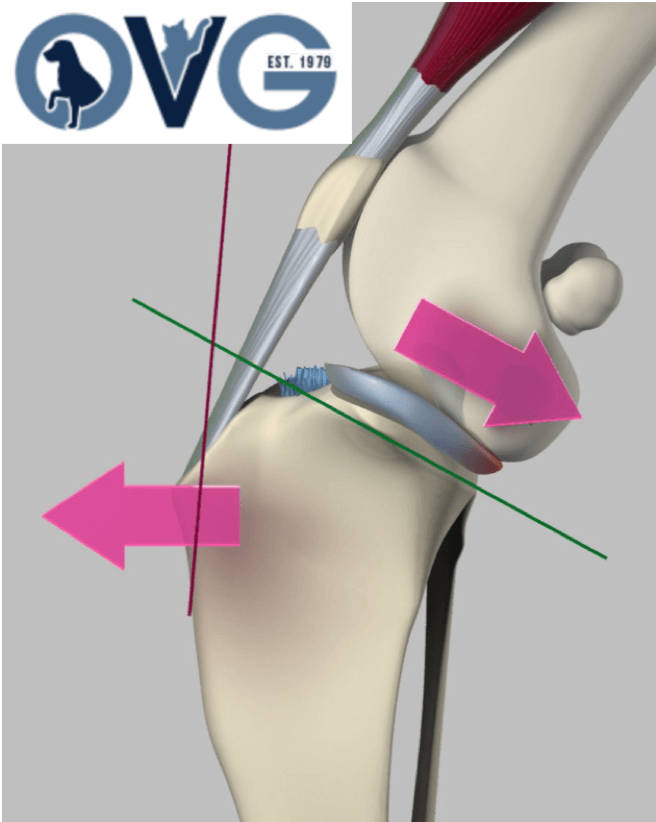

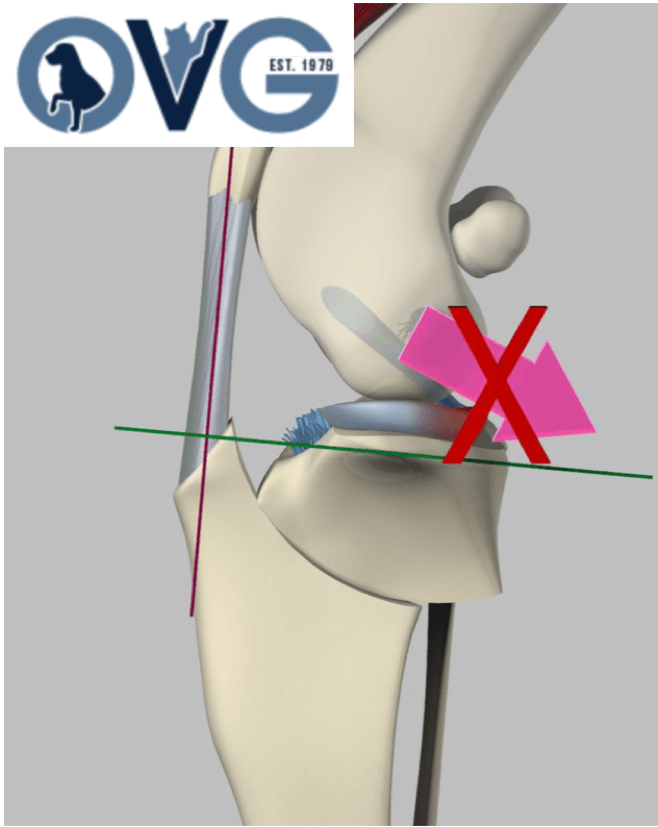

Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO)

- The top of the tibia (shin bone) is cut, rotated, and stabilised with a plate and screws.

- This changes the shape of the knee so that it no longer relies on the CrCL to be stable.

- Benefits: excellent stability, especially for active or larger dogs; high success rates for return to good function.

- Typical candidates: medium–large, athletic, or working dogs, and many smaller dogs as well.

Other Techniques (e.g., Lateral Suture / Extracapsular Repair, TTA, etc.)

- A lateral suture uses a strong synthetic material placed around the outside of the joint to mimic the ligament’s function.

- Other osteotomy procedures (like TTA) also change the biomechanics of the joint.

We will discuss which surgery is most appropriate for your dog, taking into account their size, lifestyle, and your goals.

|

|

|

2. Conservative (Non-Surgical) Management

In some cases – for example, very small dogs, dogs with serious health issues, or owners who are unable to pursue surgery – we may discuss conservative management, which can include:

- Strict activity restriction (controlled lead walks only)

- Weight management (getting to or keeping an ideal body condition is critical)

- Pain relief and anti-inflammatory medication

- Joint supplements (e.g. omega-3s, glucosamine/chondroitin)

- Physiotherapy/rehabilitation exercises

Conservative management may improve comfort, but the knee is usually less stable compared with surgical options, and arthritis often progresses more quickly.

What to Expect with Surgery

Before Surgery

- Pre-anesthetic blood tests will be completed along with an ECG of their heart.

- Your dog will be admitted to the hospital and receive pain relief and sedation before surgery.

During Surgery

- The procedure is performed under general anesthesia.

- The joint is inspected; any damaged meniscus is treated; and the chosen stabilization procedure is carried out.

- X-rays are repeated after the operation to check implant positioning.

After Surgery (Hospital Stay)

- Most dogs stay in the hospital for 1 day while their epidural pain relief wears off.

- We monitor pain levels closely and adjust medications as needed.

- You’ll receive detailed discharge instructions on rest, bandage care (if present), and medications.

Recovery & Rehabilitation

Healing and recovery are a team effort between you and the veterinary team.

First 2 Weeks (Early Healing)

- Strict rest: no running, jumping, stairs, or off-lead activity.

- Short, controlled lead walks only (usually just for toileting).

- Keep the surgical site clean and dry; prevent licking or chewing (use a protective collar if needed).

- Give all prescribed medications as directed.

Weeks 3–6 (Gradual Increase)

- Lead walks can slowly lengthen, if advised.

- Gentle physiotherapy exercises may be introduced.

- We may schedule a re-check and X-rays to assess bone healing.

Weeks 6–12 and Beyond (Return to Activity)

- If healing is progressing well, exercise is gradually increased.

- Many dogs return to a very good level of activity, including off-lead walks and play.

- High-impact activities (e.g., ball-chasing, agility) are usually reintroduced slowly and only after the vet confirms it is safe.

Every dog heals at a different pace. We will provide a personalized rehab plan and review your dog regularly.

Long-Term Outlook (Prognosis)

With appropriate treatment and good home care:

- Around 85–90% of dogs experience a significant improvement in comfort and function after surgery.

- Mild to moderate arthritis is still expected long-term, but most dogs can enjoy an active, happy life.

- 50% of dogs that tear the CrCL in one knee will eventually injure the ligament in the other knee at some point in the future, due to the underlying degenerative process.

Keeping your dog slim, fit, and well-exercised (once healed) is one of the best ways to protect their joints.

How You Can Help Your Dog

Owners play a vital role in success:

- Follow rest and activity instructions closely

- Give medications exactly as prescribed

- Attend all re-check appointments and X-ray visits

- Maintain a healthy weight – ask us if you need a weight-loss plan

- Consider joint supplements and, where appropriate, physiotherapy/hydrotherapy

If at any point you notice:

- Sudden worsening of lameness

- Swelling, redness, discharge, or your dog chewing at the wound

- Reluctance to use the leg after previously improving

Please contact us straight away.

Frequently Asked Questions

Answers to some of your most common questions:

Is my dog in pain with a CrCL tear

Yes. CrCL tears are painful, especially in the early stages. Pain can sometimes seem to improve as your dog adapts, but the joint remains unstable and arthritis continues to develop.

Will my dog be able to walk normally again?

Most dogs do very well after surgery and return to a near-normal level of activity. Some may have a slight limp after intense exercise, especially if arthritis is advanced.

Is surgery always necessary?

Not always – but in most medium and large dogs, surgery provides the best chance of long-term comfort and function. We’ll discuss all suitable options for your dog.

How long will my dog need to rest?

Plan on 8–12 weeks of controlled recovery, with the strictest rest in the first few weeks. Activity is gradually increased based on healing.

How much does cruciate surgery cost for dogs?

Costs vary between clinics and by procedure (TPLO vs lateral suture, etc.), but it is usually a significant investment. We’re happy to give you a personalised estimate after examining your dog and discussing which surgery is most appropriate.

Is my dog too old for cruciate surgery?

Age alone isn’t a reason to avoid surgery. We look at your dog’s overall health, heart, lungs and lifestyle. Many older dogs do very well after surgery and enjoy a much better quality of life once the painful, unstable knee is treated.

Can a cranial cruciate ligament tear heal on its own without surgery?

The ligament itself does not repair or “grow back”, and the knee usually stays unstable. Some small, calm dogs can cope with conservative management, but most medium and large dogs do better and stay more comfortable with surgery.

What are the risks or complications of cruciate surgery?

As with any surgery there are risks, including infection, delayed healing, implant problems, or ongoing lameness. Serious complications are uncommon, and we take multiple precautions (sterile technique, pain control, careful aftercare instructions) to keep risks as low as possible.

Will my dog get arthritis in the knee after a cruciate tear?

Yes – some degree of arthritis is almost inevitable after a cruciate injury. Surgery doesn’t stop arthritis completely, but it slows it down and usually gives much better long-term comfort than leaving the knee unstable.

How long before my dog can go off-lead again?

Every dog is different, but many can begin carefully supervised off-lead activity around the garden at roughly 8–12 weeks, if healing is progressing well. Full, “normal” exercise (including running and playing) is usually built up gradually over several months.

Can my dog still use stairs or jump on the sofa after surgery?

In the early weeks: no stairs, jumping, or slippery surfaces if at all possible. Once healing is well underway and your vet gives the go-ahead, you can gradually reintroduce everyday activities, but jumping from heights should always be kept to a minimum.

Do knee braces or supports work for cruciate tears?

Custom braces can sometimes help in very specific cases, but they don’t replace surgery in most medium and large dogs. If you’re considering a brace, talk to us first so we can advise whether it’s realistic for your dog.

What’s the chance my dog will tear the cruciate in the other leg?

Unfortunately, because the underlying problem often affects both knees, around 40–60% of dogs will eventually injure the cruciate ligament in the other leg at some point in their life.

How can I stop my dog from jumping or running after surgery?

We’ll guide you on crate/rest area setup, appropriate leads or harnesses, and sometimes mild sedative medication if needed. Boredom-busters (Kongs, puzzle feeders, gentle training games) can also help keep your dog calm while they heal.

Will my dog set off airport scanners or metal detectors after TPLO?

The plates and screws used in TPLO are small and usually do not set off airport metal detectors. Even if they did, it’s not harmful – at most you’d just mention that your dog has had orthopaedic surgery.

Is cruciate disease the same as a sports injury in people?

In people, ACL tears are often sudden sports injuries. In dogs, cruciate tears are usually due to a slow, degenerative change in the ligament, which then tears during normal activity – so it’s not usually one dramatic accident.

Can diet or supplements help my dog’s knee?

A good weight-control diet is one of the most powerful tools we have. Joint supplements (like omega-3s and glucosamine/chondroitin) can also support long-term joint health, especially alongside appropriate surgery and physiotherapy.

When to Contact Us

Please get in touch if:

- Your dog is suddenly lame on a back leg

- The lameness is getting worse or not improving

- You’ve noticed ongoing stiffness or difficulty rising

- Your dog has previously had a CrCL tear on one side and is now lame on the other

Oakdale Veterinary Group is here to help you understand your dog’s diagnosis and choose the best treatment plan.

Call us at (209) 847-2257 or book an appointment online for a knee assessment.